Go where it is darkest: When company, country, currency and commodity

risk collide

I believe that you learn valuation by doing,

not talking, reading or ruminating about it. It is natural to want to value companies

where there is a profit-making history and a well-established business model in

a mature market. You will have an easy time building a valuation model and you

will arrive at a more precise estimate, but not only will you learn little

about valuation but it is unlikely that you will find immense bargains, because

the same qualities that made this company easy to value for you also make it

easier to value for others, and more importantly, easier to price. I believe

that your biggest payoff to valuation is in valuing companies where there is

uncertainty about the future, because that is where people are most likely to

abandon valuation first principles and go with the herd. So, if you are a long-term

investor interested in finding bargains, my advice to you is to go where it is

darkest, where micro and macro uncertainty swirl around every input and where

every estimate seems like a stab in the dark. I will not claim that this is

easy or comes naturally to me, but I have a few coping mechanisms that work for

me, which I describe in this paper.

While I enjoy valuing companies with

uncertain futures but there are cases where my serenity about valuation is

disturbed by the coming together of multiple uncertainties, piling on &

feeding of each other to create a terrifying maelstrom. In this post, I

want to focus on two companies, one Brazilian (Vale) and one Russian (Lukoil), where the confluence of bad corporate governance,

a spike in country risk, currency weakness and plunging commodity prices have

conspired to devastating effect. You could adopt the lazy & very dangerous

contrarian strategy that Vale and Lukoil must be

cheap simply because they have dropped so far but I don't have the stomach for

that. I do believe, though, that if I can find ways to grapple with this risk,

there may be opportunity in the devastation.

Background, history and

market standing

Vale is one of the largest

mining companies in the world, with its largest holdings in iron ore,

incorporated and headquartered in Brazil. Vale was founded in 1942 and was

entirely owned by the Brazilian government until 1997, when it was privatized.

In the last decade, as Brazilian country risk receded, Vale expanded its

reach both in terms of reserves and markets well beyond Brazil, and its market

capitalization and operating numbers (revenues, operating income) reflected

that expansion.

Notwithstanding this long-term

trend line of growth, the last two years have been a difficult period for Vale,

as iron ore prices have dropped and Brazilian country risk has increased

(leading into a presidential election that was concluded in October 2014). The

graph shows Vale's stock price over the last 6 months (and contrasts it with

another mining giant, BHP Billiton).

Lukoil

is a Russian oil company that has seen its profile, market capitalization and

revenues rise as Russia's oil production has surged. While the company is not owned by the

Russian government, it does have close ties to the Russian power structure and

that connection, which has served it well during its lifetime, has become a

liability in the aftermath of the Russian adventure in the Ukraine, compounded

by the collapse of oil prices in the last few weeks:

Though there are

fundamental reasons for the stock price decline at both Vale and Lukoil, the fear factor is clearly also at play, because

these companies are exposed to risk not only to commodity and country risk but

there are also significant concerns about corporate (or is it political)

governance at both companies as well as currency risk factors (as both the

Brazilian Real and the Russian Ruble have slid over the last few months).

Corporate governance risk

In a post on Alibaba, I made the argument that corporate governance

affects value by making it more difficult (if not impossible) to change

management, and thus increasing the risk that a company that embarks on the

wrong course may continue on that path unchecked. With both Vale and Lukoil, there are both explicit and implicit reasons to

believe that investors in these companies will have little or no say in how the

company is run.

The place to start

analyzing corporate governance is the ownership structures of the company. With

Vale, the first sign that corporate governance is weak is the fact that they

have two classes of shares (and yes, I would make this argument about Google

and Facebook as well). In the graph below, I break down the top stockholders in

both classes.

Vale is effectively run by Valepar, which is a shell entity controlled by seven

investor groups. If you own Vale shares, as I do, it is very likely that you

own the non-voting preferred shares and that you have no say in who sits on the

board of directors and how the company is run. There is also a wild card

in this equation in the form of a golden share that is owned by the Brazilian

government, giving it veto power over major decisions and the line between

corporate and political governance becomes a fuzzy one. While Vale is nominally

an independent company, the Brazilian government reserves the right to intrude

on its management, and that power can be used to good and bad effects. The

positive is that it gives Vale a leg-up on competition in Brazil, giving it

first dibs on Brazilian reserves of iron ore, and the negative is that the

company can become a pawn in political games. Much of Vale's success in the last

decade came from a willingness on the part of the Brazilian government to give

it free rein to be run as a profit-making entity, but the machinations leading

up to the last election (where the incumbent, Dilma Roussef, was viewed as more likely to interfere in the

company's operations) have taken their toll. (The damage has been even greater

at Vale's dysfunctional twin, Petrobras, Brazil's

other large natural resource giant).

Lukoil's

ownership structure provides some clues to both why it has been successful and

the potential corporate governance nightmares ahead. The good news is that Lukoil has only one class of shares outstanding, with equal

voting rights, but the bad news is that it is not quite clear whether you will

ever get to vote for meaningful change (making it akin to a Russian political

election):

The lead stockholder is Vagit

Alekperov, formerly Russian deputy minister for oil

production. It is entirely possible that he accumulated substantial knowledge

about the oil business, while in the ministry, and brought that knowledge and

entrepreneurial zeal into play in founding Lukoil,

but it is also likely that he used his connections with the power elite to get

reserves at well below fair-market prices in building up the company which

would make him obligated to maintaining good relations with the inner circles

of Russian government. In September 2004, ConocoPhilips

bought 7.6% of Lukoil's shares to create what it

termed a strategic alliance, which it increased to close to 20%, before selling

its stake in 2011 at an undisclosed price, partly to Lukoil

and partly in the open market. As with Vale, the line between corporate and

political governance is a gray one at Lukoil, and if

you are considering buying shares in the company, it should be with the

recognition that you will have no role in how the company is run (no matter

what you read about corporate governance on the company's website).

Country risk

While investing is

always risky, it is riskier in some countries than others, partly because of

where the country is in terms of its life cycle (with growing emerging markets

being more volatile than established mature markets), partly because of the

overlay of political risk in the country and partly because of the

effectiveness or lack thereof of legal protection and enforcement of property

rights. Consequently, when valuing companies, you have to factor in where the

company operates to measure its exposure to country risk.

As a commodity

company, Vale does sell into a global market and as a producer of iron ore, it gets a significant portion of its revenues from

China (the largest consumer of iron ore in the world). The country of

incorporation in Brazil, and Vale is exposed not only because a significant of

the proportion of its reserves are in Brazil, but also because the government

has significant powers in the day-to-day running of the business. Not

surprisingly, Vale has been impacted by changes in perceptions of Brazilian

country risk. Using the sovereign CDS spread for Brazil as a proxy for country

risk, and looking at the last decade:

As Brazilian

country risk has declined over the last decade, Vale benefited, but country

risk is a double-edged sword. As Brazilian country risk has risen in the last

few weeks, Vale has felt the pain in the market:

It goes without

saying that Lukoil, which has 90.7% of its reserves

in Russia, is affected by Russian country risk. Here again, the last decade has

been a good one for both Russia and for Lukoil, as

lower country risk (measured with the CDS spread) for the former has gone with

higher market capitalization for the latter.

To investors who

were expecting more of the same, this year must have been a shock, as Russian

country risk surged in the aftermath of the events in the Ukraine.

Currency risk

When

valuing individual companies, it is generally good practice not to be a

currency forecaster and to value the company based upon prevailing exchange

rates (current and forward, from the market). It is also undeniable that

currency movements in your favor will make a bad investment into a good one,

just as currency movements against you can turn a good investment into a bad

one.

With

Vale, the stage was set in a decade where the Brazilian Real strengthened

against the US dollar, even though inflation in Brazil was much higher than

inflation in the US. As with country risk, the currency risk dragon has turned

on investors and the last few weeks has seen a meltdown in the value of the

Brazilian currency.

The story is similar for Lukoil. A decade of a strengthening ruble, in spite of

fundamentals that would suggest otherwise, has been followed by the collapse in

the last few months.

It is not clear what the

effect of a weakening currency will be on both companies. To the extent that

their reserves are in Brazil (at least for iron ore, for Vale) and in Russia

(for Lukoil), the costs are in the local currency but

their revenues are in global markets, denominated in US dollars. Thus, a

weakening of the currency can improve profit margins.

Commodity risk

Do

commodity prices affect the value of commodity companies? Stupid

question, right? Of course, they do, but the degree of impact can vary

across companies. Higher commodity prices will generally push up revenues and

to the extent that the cost of developing reserves stays stable, operating

margins will increase. In some cases, though, and especially so with oil

companies, the government can use a heavy hand (see political risk in the

corporate governance section) and force the company to sell oil at subsidized

prices to consumers in the country, effectively creating a subsidy cost for the

company that will increase with oil prices. (That is a problem at Petrobras, for instance).

Vale's

fortunes have risen as the Chinese economy has grown, primarily because China

has become the largest consumer of iron ore in the world. It is robust Chinese

growth that lifted iron ore prices in the last decade to hit highs in 2011, but

that engine has slowed and as it has, iron ore prices have dropped in the last

two years:

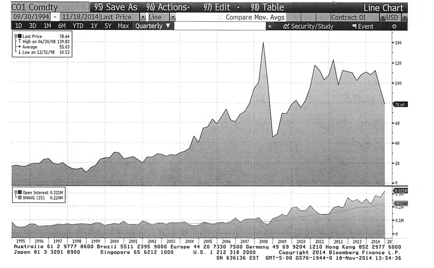

Lukoil

also benefited from the increase in oil prices in the last decade, driven

partly by geopolitics and partly by the explosive surge in automobile sales in

emerging markets.

Here

again, though, the last few months have seen a decline in oil prices to less

than $80/barrel.

While

it is easy to make the argument that commodity prices move in cycles and what

goes down has to go back up again, these cycles are unpredictable and have very

long lead times. Thus, you could have spent the entire 1980s waiting for oil

prices to go back up, just as you would have waited the entire last decade for

the drop back in prices.

Valuing Vale

The value of Vale is

affected by all of the above: its value is a function of company, country,

currency and commodity risks. To capture the effects, I valued Vale in US

dollar terms and assumed that Vale was a mature company, growing at 2% a year

in perpetuity. I varied the following inputs:

1. Operating

income: The operating income in the trailing 12 months,

through November 2014, was $12.48 billion, well below the operating income in

the last fiscal year ($17.6 billion) and the average operating income over the

last five years ($17.1 billion).

2. Return

on capital: The return on capital in the last 12 months was

11.30%, higher than the cost of capital that I estimated of 8.59%, but lower

than the return on capital in the most recent fiscal year (14.90%) and the

average over the last five years (18.22%)

To estimate the cost of

capital, I built off the US 10-year treasury bond rate as the risk free rate

and used an equity risk premium of 8.25%, reflecting a weighted average of the

equity risk premiums across the countries where Vale has its reserves (60% are

in Brazil). You can check out the spreadsheet yourself and change the numbers.

Varying the numbers, I get

the following estimates of value per share for Vale.

|

Last 12 months (11.30%) |

Last fiscal year (14.90%) |

Average of last 5 years (18.22%) |

Equal to cost of capital |

|

|

Last 12 months

($12,475) |

$20.55 |

$21.83 |

$22.57 |

$18.87 |

|

Last fiscal year

($17,596) |

$30.69 |

$32.50 |

$33.53 |

$28.32 |

|

Average of the last

5 years ($17,119) |

$34.12 |

$36.11 |

$37.25 |

$31.52 |

I am sure that I am

missing something but at the stock price of $8.53 on November 18, 2014, it seems like it is grossly

under valued.

Valuing Lukoil

I

followed a similar path for Lukoil, varying operating

income and return on capital, while valuing the firm as a stable growth firm

(with a 2% growth rate) and with a cost of capital that reflects an updated

equity risk premium for Russia (9.50%).

|

|

Last 12 months

(11.71%) |

Last fiscal year

(12.04%) |

Average of last 5

years (14.32%) |

Equal to cost of

capital |

|

Last 12 months

($11,803) |

$80.81 |

$81.32 |

$84.24 |

$80.45 |

|

Last fiscal year

($12,808) |

$88.60 |

$89.16 |

$92.32 |

$88.21 |

|

Average of the last

5 years ($12,744) |

$88.10 |

$88.66 |

$91.81 |

$87.72 |

At $45.30 a share on November 18, 2014, I am again

either missing something profound or the stock is massively under priced.

What now?

It is easy to come up with reasons not to buy Vale

and Lukoil right now and wait for things to get

better. That is precisely why I already own Vale (and I am not in the least bit

ashamed to admit that I bought my shares at $12/share) and plan to add to my

holdings. I plan to buy Lukoil to my portfolio, and

live with the discomfort of having no power to exert change. After all, at the

right price, you can live with a lot of discomfort.